I know, I know, she's not a sea kayak ...

... but she's mine, and I want to know more. She was built in 1934, and she may be the last of her kind.

... but she's mine, and I want to know more. She was built in 1934, and she may be the last of her kind.

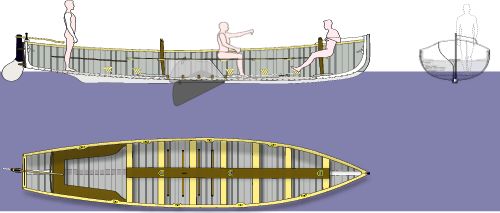

She's a Royal Navy 30 foot gig, like Robin Burnham's great model in the picture above. According to the Admiralty Manual of Seamanship the 30 foot gig was "the fastest type of service boat under sail". Under oars too. The gig was only 6' wide, fitted with two masts and a steel centreplate / drop keel, not just fast but as seaworthy as a shallow-draft open boat can be.

A big warship would have carried a number of different open boats. One of these is well known because of its later use by sea training organisations: The Montagu or Montague whaler was quite similar to the gig, a rowing-sailing boat about 6' wide, but lighter and shorter at 24' or 27' long. Both the naval whalers and 30' gigs were carried on the decks of warships. They were used to go from ship to shore, and for training in seamanship, rowing and sailing, and as service boats in dockyards. A captain or admiral would have had his own gig with a smart boat's crew. A major warship would have carried a gig overseas, maybe nested inside the 32' cutter while not in use. If you can tell me more about Navy gigs, please get in touch.

I think the gig is spectacularly good-looking, and this one is in good condition. As soon as I bought her I wrote to all the maritime museums and heritage organisations I could think of, offering to sell her to them for what I paid. As there were no takers, I now sail her myself with a clear conscience. The Navy gig, with no external ballast other than a 70 lb centreplate, no decking whatever and scarcely any flotation if she filled up, was not all that safe in bad weather even with a professional coxswain and a crew of six, so some changes were necessary including partly decking her, adding positive flotation, and fitting 800 lbs of internal ballast but don't worry, all the changes are easily reversible.

I think the gig is spectacularly good-looking, and this one is in good condition. As soon as I bought her I wrote to all the maritime museums and heritage organisations I could think of, offering to sell her to them for what I paid. As there were no takers, I now sail her myself with a clear conscience. The Navy gig, with no external ballast other than a 70 lb centreplate, no decking whatever and scarcely any flotation if she filled up, was not all that safe in bad weather even with a professional coxswain and a crew of six, so some changes were necessary including partly decking her, adding positive flotation, and fitting 800 lbs of internal ballast but don't worry, all the changes are easily reversible.

She has her original teak gratings and rudder, and six long oars although not the originals. She also has her original fittings of bronze gunnmetal and brass, apart from one cleat which seems to have wandered off.

She has her original teak gratings and rudder, and six long oars although not the originals. She also has her original fittings of bronze gunnmetal and brass, apart from one cleat which seems to have wandered off.

The original service sailing rig was powerful and weatherly but tacking it took muscle and precise teamwork. The commander-in-chief at Plymouth re-rigged his 30' gig by taking two gunter rigs from RNSA 14 sailing dinghies, which made it much handier. I'll be following his lead, more or less.

Gigs were built of the best available wood, usually Honduras mahogany and teak. Some were clinker-built but many had the smooth skin of carvel construction, with longitudinal planking on the outside of the hull and a separate layer of diagonal planking on the inside, and between them a layer of calico soaked in linseed oil or paint.

Many of the carvel gigs were stitched together with copper wire using the Consuta method developed by Sam Saunders. This foreshadowed cold-moulding and was used to build boats and seaplanes. Mine's copper-nailed carvel. A boat-builder comments "The nailing was in a group of four at each plank intersection with the inside seams. These nails were all then riveted up with a boy on the dolly outside and a shipwright inside. What a job! When you looked down the length of the [boat] all you could see was a forest of sharp nails with the sun glinting off them, quite painful until you managed to clear an area around you. If you did not have large forearms before you started, you certainly did after, I could climb a 30’ rope without using my legs after six weeks of nothing but riveting all day."

Here's a general arrangement drawing which includes a small sketch of the gig's lines. Click on the little image to see that sketch at full size.

Here's a general arrangement drawing which includes a small sketch of the gig's lines. Click on the little image to see that sketch at full size.

This is very much a sailing-rowing gig, rather than a pure rowing boat. At 1.15 tons weight, she's no fairy.

This is very much a sailing-rowing gig, rather than a pure rowing boat. At 1.15 tons weight, she's no fairy.

I would very much like to find out more about these boats (scantlings, construction details, performance under different sailing rigs, history, anecdotes).

Below is another photo of Robin's model, at an earlier stage in construction and at an angle that really shows off the curves of the navy gig.

John Leather's excellent book Sail & Oar has a chapter about gigs in which he talks about Uffa Fox and the 25' gig from the royal yacht Britannia. Uffa re-rigged her with a foremast and sails from his racing dinghy Avenger (often called the world's first planing dinghy) and the rig from his racing canoe East Anglia as a mizzen. "Now in her 46th year, her yawl rig gave her a new lease of life and she bounded along with the grace and ease of a greyhound. When reaching off the wind she came clean out of the water to the mainmast". John Leather himself had a passionate affair with a gig and said "in a fresh wind and a long sea... a gig under sail seems to fly along like a seabird, the water strumming under her lee side and the long, lean bow slicing through the crests". In Uffa Fox's own book Sailing, Seamanship and Yacht Construction he talks about his adventures sailing Valhalla's 30'6" whaleboat. At the time of writing, you can read that chapter on Google Books.

That's the summer-weather side of sailing these gigs. For the all-year-round view there's the Admiralty Manual of Seamanship for 1937 and the 1941 classic Sea-boats, Oars & Sails by Conor O'Brien.

For sailing, a gig needs either a full crew or some form of ballast. The Admiralty Manual gives general advice about sailing service boats: "When blowing hard take a full crew and extra barricoes filled with water". A barricoe (pronounced 'breaker') is a 4-6 gallon cask. The Manual gives specific advice about sailing the gig's big sister, the the 32 foot cutter: "It is always advisable to have plenty of ballast : in a strong breeze two rum casks should be filled and lashed just abaft the mast, in addition to the boat's breakers. These boats become very hard to handle in a strong breeze if they are not properly ballasted, as having but little hold in the water they are blown bodily to leeward, and will continually miss stays in tacking through being unable to carry their way through the water." A gig's normal crew is six plus coxswain. Say 7 x 160 lbs = 1120 lbs for crew weight. 55-65 lbs each, 4 x 65 lbs = 260 lbs. 1120 + 260 = 1380 lbs. Live ballast is more effective than static ballast because it's always to windward. A gig would also have been carrying between one and five passengers weighing 160-800 lbs in total. Say 1700 lbs or 771 kg.

Conor O'Brien designed the 42' yacht Saiorse and sailed her round the world in 1923-25. He was a delivery skipper for merchant navy ships in WWII, but some of WWI he spent on war service sailing long, slim open boats in winter in the exposed waters of the North Atlantic coast. O'Brien was an architect by training, later a gun-runner for Irish independence who might have shared the fate of Erskine Childers, author of Riddle of the Sands, but survived to become a mainstream politician and author of fourteen books. He was also a talented amateur naval architect, and he writes about boats with an excellent, perceptive style. In Sea-boats he gives detailed, practical advice about rigging and sailing 20' and 24' open boats, often solo. It may be of interest to the new wave of sail-and-oar sailors and raid competitors because he wrote at a time when the traditional sailing rigs of working craft were still all around, but so were inboard and outboard motors, and aircraft technology applied to boats, and planing dinghies with modern sailing rigs.

Here are some extracts from Sea-boats, Oars & Sails, starting off with a note about ballast. Conor O'Brien's 24 foot whaler sailed in very exposed waters and carried "nearly half a ton of crew and ballast ... we carried 5 cwt. [254kg] in the form of iron 56 lb. weights, rectangular with fixed handles, very handy for trimming - we trimmed them across when tacking - and useful for mooring, but it was not enough when I was alone in her ... shingle in small sacks makes the best ballast."

"The sailing boat referred to in this book, which excludes all racing craft, is not a miniature yacht. Their functions are different: the boatman is dependent on the shore, and has to make his port in good time, the yachtsman can keep the sea as long as he likes."

On the other hand, a yachtsman has to anchor or stay on a mooring, which means mucking around with a dinghy ever time you want to get ashore, or at a marina dock. If you sail a boat which will float in knee-deep water, you can slip into the mouth of a narrow river or upstream under a bridge, or just sail her up a deserted beach at high tide and enjoy the luxury of stepping over the side dry-shod to explore.

"... a sailing boat, as I define the term, is not merely a small yacht stripped for action. The significant difference is in the method of handling them. The yacht is almost uncapsizable, and, if luffed head to wind, heavy enough to carry her headway for some little time after the sails have ceased to draw. The boat stops immediately the propelling force fails... in a boat, the main sheet must be held in the hand, and with it she is played through a squall as a fish is played with rod and line, while she is kept sailing smartly all the time. It is fatal to luff, for if she loses headway she will not recover it till she has fallen off broadside to the wind, and if she is caught in that position with no way on she is easily capsized."

So you mustn't be asleep under way. On the other hand, a boat will sail over most rocks that don't show a swirl on the surface, and can be inshore keeping company with sea kayaks, whereas the prudent yachtsman stays well away from shores, headlands and any possible reef or mudbank.

"... my whaler felt perfectly safe at twelve [knots] with the wind on the quarter, provided there was room to run her off dead before the worst seas... A long boat, having easier lines, does not want as much sail to drive her as a shorter one of the same weight; and since her sail can be spread out fore and aft instead of towering upwards, her lack of beam is no disadvantage. Her length allows fine lines aft, and the stern is generally allowed to be the most important part of any craft, though, because it is the custom to sell boats by length, it is often docked most objectionably for the sake of economy"

He didn't feel that an engine was necessary in a boat less than 25' long and less than a ton in weight. "In most cases it is a waste of time to try to sail a boat dead to windward if she is light enough to row and conveniently arranged for that end; and nothing gives such control or power of manoeuvring in awkward places as a pair of oars".

"Personally I would keep the canvas of any boat low, so as not to impair her stability, for I want plenty of it, to take advantage of a fair wind, since windward work is apt to be unprofitable ...the sail of an open boat must come down instantly, and must not come down all over the helmsman's head. Too often this is a pious hope, and the man who sails alone is taking serious risks; which is absurd, for the function of sails is to enable him to proceed when he cannot get a crew to help him with the oars. Let him make his rig safe, or scrap his sails and buy a motor."

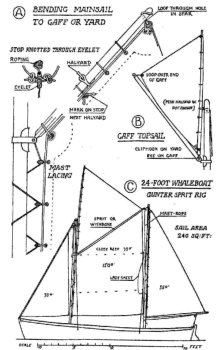

Here's the rig for his 24 foot whaler. By using gunter rig, Conor O'Brien was able to keep the spars short enough to take down at sea. His view was that if you expect to make progress to windward under oars, you want to take down and stow not only your sails but your masts too.

Here's the rig for his 24 foot whaler. By using gunter rig, Conor O'Brien was able to keep the spars short enough to take down at sea. His view was that if you expect to make progress to windward under oars, you want to take down and stow not only your sails but your masts too.

"My twenty four-foot whaler was my ideal sailing boat, but we nearly always managed to keep her afloat. If we were left on a sandy beach we were in trouble, because even with all the ballast and spars out of her she was too heavy to move, and of course hauling her up was out of the question. Two of us could handle that twenty-footer I mentioned on a beach, and beaching, if there is any surf, requires a crew of two, even for a much smaller boat, so it looks as if 20 feet was a suitable maximum for that sort of work. She was a very able boat, and put in some hard war-service in a Hebridean winter, though I never had quite the same confidence in her as in the larger whaler.

Both of these were entirely open boats, with no other additions than their centreboards, with the help of which they would work to windward fairly well against the big seas of the Atlantic and even against the chop in the Minch, and they were incredibly fast off the wind."