A very safe sport

"Sea kayaking is not inherently dangerous. However to keep safe and avoid accidents, it requires a sound knowledge of the environment and of the sport in addition to a good attitude”. Canadian Coast Guard Sea Kayaking Safety Guide, 2003.

Sea kayaking is a very safe sport as long as you are properly trained and equipped. Good training and advice is available for free in many kayak clubs. One thing you learn with a club is not to push your limits too far, too fast. The result is that thousands of competent kayakers of all ages play safely on surf and white water, including Alpine snow-melt rivers, all year round.

More deaths and injuries are caused in Britain by pillows, telephones and flowers than by all forms of kayaking put together. www.hassandlass.org.uk. It is so difficult to get hurt while kayaking that including extreme white-water and "drunken non-swimmer in borrowed kayak" incidents, there are typically only 4 kayaking deaths in Britain every year and very few serious injuries. Compare that with riding a bicycle, for which the annual toll is 150 killed, 2,200 seriously injured, and 14,000 with mild to moderate injuries.

Sea kayaking is much safer than horse riding, scuba diving, motorcycling or paragliding. If you have adequate training and equipment, if you spend most of your time in estuaries, go out round the headland only in good weather, and don't feel the urge to surf over reefs, there's no reason why you shouldn't go sea kayaking safely all your life. Even if you like to take risks, it's difficult to get hurt.

The everyday risks of a kayak trip are not waves, overfalls or whirlpools but:

• Driving from home to the beach

• Falling over after slipping or tripping

• Hurting your back by heavy lifting

• Standing on something sharp in bare feet

• Sunburn

The risk of dying while sea kayaking is vanishingly small. Of course, although fatal incidents are rare they stick in your mind. Nearly all are caused by cold water. In some of these cases, the deceased was an adventurer or explorer in the truest sense and we salute their spirit, courage and endurance. But most of those incidents would have been avoided by the use of adequate equipment, skill and care. And these are not difficult things.

There's nothing wrong with carrying distress signals, but safety does not come in a box, and carrying safety equipment can make you over-confident. Click here for a comment about the Talisman Effect.

If you organise or lead kayaking trips, see Risk Assessment.

When you're no longer a novice following your leader like a duckling, you should always be aware of other boats that may run you down; the sea for a mile ahead in case of boomers or surf; the sky for five miles to windward for dark cloud indicating the approach of strong winds or line squalls; your position relative to your start point and destination; the likely effect of any local currents; and your actual present rate of progress over the ground.

Cold shock, swim failure & hypothermia

Most sea kayaking takes place on water at or below 16 degrees centigrade (60 degrees fahrenheit) where cold is a real hazard.

Let's not exaggerate. 16°C is about as warm as the sea ever gets in Britain but that doesn't stop kids swimming in summer. For a fit, experienced, well-equipped and properly trained kayaker the risk of being overcome by cold is very small. However immersion in cold water is the main cause of death for sea kayakers, and cold shock does occasionally kill a highly competent kayaker before nearby friends can retrieve him.

The solutions

The risk can be virtually eliminated by these precautions:

• Wear kayak clothing which will keep you comfortable in your kayak, and reasonably comfortable during a 15-minute immersion.

• Practice your kayak roll until it works automatically, every time, at sea and in the surf zone.

• Know your limitations, and when you extend them do so little by little. For novice and intermediate kayakers, this means going out with other kayakers rather than solo, avoiding areas which are exposed to strong winds, and thinking twice before entering fast-moving water and areas of large breaking waves.

• Practice deep-water rescue until you can get a casualty out of the water in twenty seconds and back in his/her kayak in less than two minutes.

• Ensure that your body is acclimatised to cool or cold water.

• Stay fit. Staying young would be good too, but keeping acclimatised to cold water is an effective alternative.

Sea temperatures

| |

Fresh water freezes |

Human body temp |

Water boils |

| Celsius/centigrade |

0°C |

37°C |

100°C |

| Fahrenheit |

32°F |

98.6°F |

212°F |

Here are a few sea temperatures from round the world:

| Surface sea temperature |

Winter/Summer (°C) |

| Greenland |

Ice / 03 |

| Anchorage, Alaska |

-1 / 14 |

| Maine, USA |

01 / 17 |

| Vancouver |

07 / 14 |

| Scotland |

07 / 13 |

| England |

07 / 16 |

| Oregon |

09 / 14 |

| Wellington, NZ |

11 / 17 |

| New York |

02 / 22 |

| Southern California |

14 / 20 |

| NW Mediterranean |

12 / 25 |

| Sydney, Australia |

18 / 23 |

| Hawaii |

22 / 26 |

| Miami |

21 / 30 |

| Cuba |

26 / 29 |

Sea temperatures vary more over a short distance than you might expect. Water in an estuary may be particularly cold in winter when snowmelt comes down the rivers, and particularly warm in summer. On the sea in summer, surface water at a beach or in a sheltered bay may be warmed by long hours of direct sunshine. There is often a very marked vertical temperature range so that a swimmer treading water in the middle of the bay would find the temperature pleasant on the surface, chilly at waist level, unpleasantly cold round the ankles, and cold everywhere if (s)he swims out to sea.

This is how the average swimmer perceives sea temperatures (click here for air temperatures):

| Sea temperature |

(°C) |

| Most people feel comfortable when swimming |

21 or more |

| Some people feel fairly comfortable swimming |

17 - 20 |

| Most people feel the sea is cold |

12 - 16 |

| Everybody feels the sea is very cold |

11 or less |

| Immersion is painful |

7 or less |

| Dipping any part of the body is painful |

4 or less |

In the summer seas of northern Europe, including Britain, an adult kayaker in light summer clothing who is hanging onto their boat waiting for help, inactive, may find it difficult after 15 minutes to do much with their hands or even their arms. They may be unable to do anything useful after 30 minutes, and unconscious in 2 hours.

In the winter seas around Britain, a person who is inadequately dressed may be helpless in as little as 3 minutes and dead in 30.

White-water kayakers and winter surfers often get hit in the face by water below 8°C (46°F). It goes in your ears and down your neck. Sometimes it blasts up your nostrils or squirts between tightly-closed eyelids. If you capsize into water below 6°C it is hard to think for a moment and then it feels as if somebody is tightening up a woodworking vice on your face. If you capsize into water at 2°C it feels as if somebody is trying to remove your face with abrasive paper. But it doesn't kill you, as long as you are properly equipped, dressed and trained - and acclimatised.

With the right clothing and skills, you can be warm and happy during a surfing session even when air temperatures are cold enough to turn your wetsuit into a crunchy icicle if you take it off during the lunch-break. And you can at least stay functional despite having your boots freeze to a rock while you are standing there with a rescue throwline.

The real hazard

Your editor thought he knew quite a lot about the effects of cold water.

Your editor thought he knew quite a lot about the effects of cold water.

After all, he has spent a fair bit of the last thirty years upside-down in North Atlantic winter surf and Alpine rivers, and has the unusual distinction of having nearly been buried when a snowbridge across the Clarée collapsed into the river during an off-season descent (made a change from skiing).

He thought a kayaker had to watch for hypothermia but that cold shock was not a real issue if you were competent and properly equipped. After all, he reasoned, you don't find a line of ambulances waiting by Cornish surf beaches in January or alongside snowmelt rivers in the Alps.

Your editor was totally wrong. Cold shock is the killer for those who do water sports in a cool climate. Dr Howard Oakley kindly put him right and made textual suggestions. Dr Oakley is head of Survival & Thermal Medicine at the Royal Navy's Institute of Naval Medicine. Any remaining errors, of course, are the fault of your editor.

Cold shock can become a real problem in a few seconds. It is probably responsible for most of the serious or fatal incidents that follow sudden immersion in water below 16°C (60°F). It explains the stories you hear about helicopter crews who ditch in cold seas and fail to get as far as the exit, people trapped under inverted boats because they were unable to hold their breath for the few seconds it would take to duck under the gunwale, and strong swimmers who are overcome before completing a thirty-metre swim for the shore.

This is what happens when an adult suddenly enters water which is colder than your clothing and acclimatisation can handle:

Phase 1 - the first three minutes. Cold shock.

Phase 2 - the next thirty minutes. Swimming failure.

Phase 3 - after thirty minutes or more. Hypothermia.

Phase 4 - post-rescue collapse. Casualties with hypothermia often collapse and sometimes die while being retrieved, during re-warming or within a few hours afterwards. See Treating A Hypothermic Kayaker.

To put it another way, on entering cold water a person in light clothing will usually experience very marked cold shock within the first 30 seconds to 3 minutes. Within 3-30 minutes that person would experience swimming failure. After 30 minutes in cold water, hypothermia becomes a factor.

Survival instructors use the Royal Navy training DVD Cold Water Casualty. It shows former British Olympic swimmers Duncan Goodhew and Sharron Davies. Neither wore any protective clothing. She was asked to swim in a pool at 10°C. She was visibly in trouble after 8 minutes and had to give up at 10 minutes. He was strapped to a seat, given an aqualung and immersed in water at 5°C. Immediately he was visibly distressed, and he had difficulty undoing the seat-belt release buckle.

Cold shock

"The sudden lowering of skin temperature on immersion in cold water represents one of the most profound stimuli that the body can encounter"

Golden & Tipton, Essentials of Sea Survival (Human Kinetics 2002)

If you are used to immersion in cold water, you can walk into the English Channel on New Years Day and enjoy a swim when the sea temperature is 7°C. Plenty of British people do that anyway, fuelled by alcohol. With rare exceptions, they get away with it. However if you jump into water which is colder than you are used to, your body may react strongly and in a way which puts your survival in doubt.

The colder the water, the more care you need to take. A training video for commercial fishermen in British Columbia states that the local average water temperature is 4.4°C, with the result that cold shock accounts for about half of deaths by drowning. Source: Safe at Sea : An Overview (2008, Fish Safe BC).

Kayakers just need to know what to wear and do to be safe, so we're not going to examine gasp reflex, mammalian diving reflex, vagal inhibition, reflex cardiac arrest or laryngeal spasm.

We do need to be aware that the shock of sudden immersion in cold water may cause the following with increasing force for 30 seconds and then for two or three minutes:

• The casualty takes a big inbreath, attempting to inhale two or three litres of air in one go. Not helpful if your head is under water. Inhaling as little as 200 ml of water can be enough to cause drowning.

• The casualty then constantly takes very rapid breaths (hyperventilation). This tends to cause feelings of suffocation, panic, dizziness and confusion. The casualty may not have enough breath control to shout for help or inflate a lifejacket. He cannot hold his breath for more than five seconds at a time, so he may inhale water if his mouth is underwater or he is trying to swim in a rough sea.

• The casualty experiences increased heart rate, irregular heartbeat and increased blood pressure. These can bring on a heart attack or a stroke, which probably kill several older kayakers every year within seconds of a capsize into cold water.

|

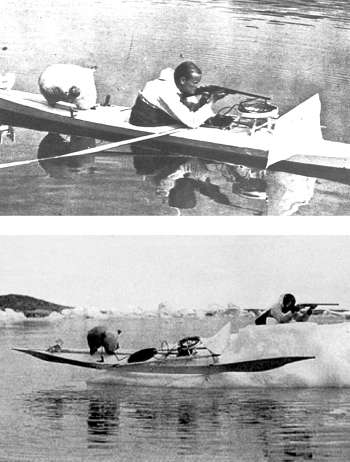

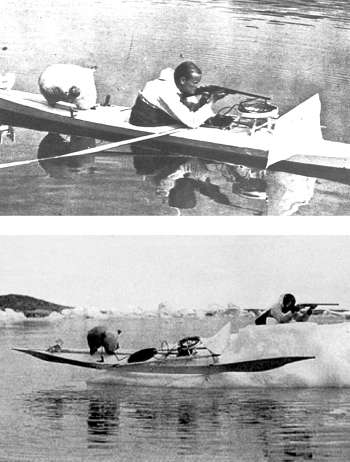

Fit, acclimatised people should not push their luck too far. The pioneer British kayaker Gino Watkins was probably overcome by cold shock in Greenland in1932 while hunting for seals on his own.

Although only 25 he was leader of the British Arctic Air Route Expedition (BAARE). The inflated skin on the rear deck is used to prevent dead seals from sinking; the white screen on the foredeck is for camouflage; and the frame behind it carries the harpoon line.

His kayak was found floating in a fjord, partly filled with water, and his trousers and spraydeck were found on an ice floe. Probably he got out of his kayak onto a floe, his kayak slipped off and started drifting away, and he stripped before diving in to retrieve it. It was late August and the water temperature would have been about 3°C.

The cold shock response can be "trained out" by accustoming yourself to cold immersion. Which is how many older people who like to swim for thirty minutes at a time in the sea around Britain can do so all year, without any protective clothing. |

|

You don't need to go to masochistic extremes to acclimatise yourself to the cold. True, if you take a two-minute cold shower each day for a week it will almost eliminate the effects of cold shock, but so will taking a few swims in the sea during a British summer. This protection can last for up to a year.

You're not going to be kayaking naked. If you're a year-round kayaker and you surf or regularly practice rolling, that should be enough to keep you acclimatised.

Many experienced kayakers like to start a winter session by splashing cold water on their faces as soon as they go afloat. White-water and surf kayakers often start a winter session with a few "high recovery" support strokes, ducking their head and one shoulder under water.

|

Swimming failure

We mentioned the Royal Navy DVD in which former Olympic swimmer Sharron Davies tried to swim in water at 10°C, to which she was not acclimatised. She was exhausted and in trouble after eight minutes and the experiment was discontinued at ten minutes.

In water which is significantly colder than you are used to, your ability to swim decreases over a period of five minutes to half an hour. Your swimming style deteriorates until you are almost vertical in the water. You cease making any forward progress, you can't raise an arm to wave for help, you can't control your breathing enough to shout, you are unable to keep your airway clear, and you drown.

Of course a sea kayaker who comes out of his or her kayak into a cold sea is probably holding onto the kayak, not trying to swim. As the casualty's hands and forearms get colder (s)he will lose strength and dexterity. (S)he will soon be unable to untie a knot and as weakness grows in the hands and arms (s)he will become unable to re-fit a spraydeck if rescued, set up a rescue outrigger for solo self-rescue, open and fire a flare, or even grab the end of a throw-line.

If the casualty is part of a group, the deterioration may make it difficult or impossible for him or her to climb back into a kayak which has been emptied by another kayaker. During deep-water exercises on cool water, remember to get the casualty out of the water as soon as possible, even if his kayak is not yet ready, and practice using a rescue stirrup.

Your editor thought he knew quite a lot about the effects of cold water.

Your editor thought he knew quite a lot about the effects of cold water.